Before you take those probiotics...

What you need to know before you swallow the microbiotics craze.

Happy Monday, health heroes — Dr. Alice Burron here from The Health Navigator Group, ready to bring a little ray of health enlightenment to your inbox on this fine Monday.

Thank you for responding to my poll last week! It looks like most of you are seeking more information on the microscopic and wonderful world of the microbiome and what all of those probiotics are really doing for your health.

Are they as helpful as we are told they are? Should we be popping a gummy or drinking kombucha every day? And what is the difference between a probiotic and a prebiotic, anyway?

Hopefully, this letter will leave you feeling a little more informed before you decide to ingest the little creatures reported to make you healthier.

Supplements are everywhere these days, and adding them to your daily routine might feel like a great idea to stay healthy and take care of yourself.

But what do you really know about probiotics, other than the overall claim that they keep your gut healthy? Let’s take a closer look at what that means, and maybe think twice before continuing to ingest those little microbes.

First, the facts:

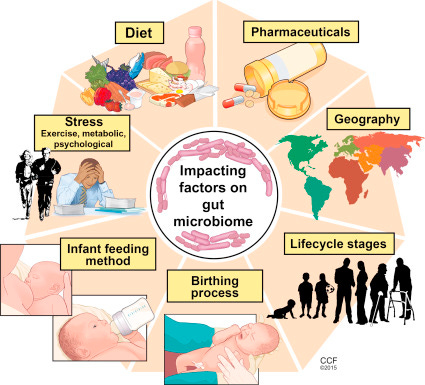

🦠 The human gut is home to a diverse community of microorganisms, primarily bacteria, but also including viruses, fungi, and other microbes. The estimated number of microbial cells in the gut is around 30 to 40 trillion.

🧬 The amount of DNA from microorganisms in our system (collectively known as the microbiome) is quite significant compared to the DNA contained within our human cells. The human genome consists of approximately 20,000 to 25,000 genes, containing around 3 billion base pairs of DNA. The microbial DNA in our gut, which includes bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms, collectively has a much larger genome size. Estimates suggest that the microbial genome (microbiome) contains over 100 times more genes than the human genome. This translates to several million genes.

🔬 99% of the genes in our body from our microbiome, not our chromosomes.

While microbial DNA does not directly integrate into our own genetic code, the activities of gut microbes can profoundly impact our physiology, immune responses, metabolism, and overall health through various mechanisms of interaction and influence.

In the book, The Human Super-Organism: How the Microbiome is Revolutionizing the Pursuit of a Healthy Life, Dr. Rodney Dietert, PhD, makes the case that if we expect our 1% of genome to exert more control than the microbial 99%, then we are delusional (my wording, not his).

Although our two genomes work together, if we introduce new organism in such a quantity as to overwrite our ancient original ones, then we’re looking at some potential impact – good or bad, probably both.

While probiotics can have been shown to have beneficial effects on gut health and immune function for many individuals, should it be taken over long periods of time? Or could it potentially alter the balance of the gut microbiome in unintended ways?

Here are a few things worth thinking about:

Microbial interactions. Introducing a new strain can alter the balance of existing microbial communities in the gut. This could potentially lead to dysbiosis, an imbalance of both beneficial and harmful microbes.

Immune response. Reactions to certain probiotic strains are actually more common than we realize, leading to immune responses or sensitivities that could manifest as gastrointestinal discomfort or other uncomfortable symptoms.

Effectiveness. Not all probiotic strains have the same effect on every individual. The response to probiotics can vary based on factors like genetics, diet, and the current state of the gut microbiome.

Competitive exclusion. Some probiotic strains may outcompete native gut microbes for resources or space in the gut environment. This could potentially reduce the abundance of beneficial or protective native microbes, altering the overall balance of the microbiome.

Niche displacement. Introducing new microbial strains creates shifts in the ecological niches within the gut. This can lead to changes in microbial diversity or function, potentially affecting the resilience and stability of the gut microbiome.

Microbial interactions: The introduction of probiotic strains could influence complex microbial interactions and signaling pathways in the gut. This could lead to cascading effects on metabolic processes, immune responses, and overall gut health.

Risk of dysbiosis. In some cases, the dominance of introduced probiotic strains or unintended microbial changes could contribute to dysbiosis, where there’s an imbalance that may negatively impact digestive function, immune regulation, or even metabolic health.

Individual variability. Responses to probiotics can vary widely among individuals due to differences in genetics, diet, health status, and baseline microbiome composition. What works well for one person may not have the same effects for another. Additionally, introducing certain probiotic strains to individuals with compromised immune systems or underlying health conditions could potentially lead to infections or exacerbate existing health issues.

Long-term effects. The long-term effects of introducing specific microbial strains into the gut are still being studied. While probiotics are generally considered safe for most people, more research is needed to fully understand their impact on gut health over extended periods. Basically — it’s too early to tell.

What’s the difference between a prebiotic and a probiotic?

You’ve seen both pre and pro-biotic supplements on shelves, but they’re not interchangeable.

Probiotics are the little creatures that live in your gut. Prebiotics are the foods these critters eat — essentially, high-fiber foods that act as food for human microflora.

They ideally should be consumed together.

Who gets a say on which microbes are added to a probiotic supplement?

Typically, these things are determined by the manufacturer or formulator, often based on several factors like:

Intended health benefits. Different probiotic strains may have specific documented benefits, such as supporting digestive health, immune function, or managing specific conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or lactose intolerance.

Scientific research. Manufacturers may choose strains that have been studied and shown efficacy in clinical trials or scientific research for the intended health benefits.

Synergistic effects. Some probiotic formulations combine multiple strains believed to work synergistically, potentially enhancing their overall effectiveness or targeting a broader range of health issues.

Stability and viability. The ability of strains to survive manufacturing processes, storage conditions, and passage through the digestive tract (survival rate) is also a consideration. Some strains may be more robust and stable than others.

Consumer preferences. Formulators may consider consumer preferences and market trends when selecting strains for a probiotic product. For example, strains that are well-known or perceived as beneficial may be favored.

Regulatory guidelines. Probiotic products are often formulated according to regulatory guidelines and may need to meet specific criteria for safety, efficacy, and labeling requirements in different countries.

Clinical expertise and formulation science. Some probiotic formulations are developed in collaboration with researchers, clinicians, or formulators specializing in gut health and microbiome science. Which ones are formulated this way? Who knows.

Meet your cast of microbiome characters.

The most common probiotic microbes belong to several genera and species of bacteria and yeast. Here are some of the most frequently used probiotic microbes.

Bacteria:

Lactobacillus — This genus includes various species such as:

Lactobacillus acidophilus

Lactobacillus rhamnosus

Lactobacillus casei

Lactobacillus plantarum

Lactobacillus paracasei

Bifidobacterium — Another common genus, including species such as:

Bifidobacterium bifidum

Bifidobacterium longum

Bifidobacterium breve

Bifidobacterium lactis

Enterococcus: Species like Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis are sometimes used as probiotics, particularly in certain formulations. They naturally live in our GI tracts.

Streptococcus: Certain strains of Streptococcus thermophilus are used in probiotic products, particularly in dairy fermentation.

Bacillus: Certain species of Bacillus, such as Bacillus coagulans, are spore-forming bacteria used as probiotics for their stability and potential health benefits.

Yeast: Saccharomyces boulardii is a common beneficial yeast often used as a probiotic to support digestive health and treat conditions like diarrhea.

That’s a lot of information. Did you know all of this before taking your probiotic? Are you aware of what each are reported to do?

Probably not, and neither do I — this is what bothers me most about probiotics. We are blindly assuming they are safe, following the rising trend.

Personally, I think focusing on prebiotics is the first choice, followed by probiotics if needed — but temporarily. It’s rare that you need to ingest probiotics all the time for prolonged periods of time. If your gut is operating well naturally, you likely don’t need probiotics.

Making Soda Healthy By Adding Microorganisms?

Today's trend is to drink other microbe-fortified sodas and foods, such as Poppy, Olipop, and even kombucha. It’s truly muddying the water in terms of the definition of “healthy.” Although these sodas might be okay now and then, is it good for people to add them regularly to their overall diet?

Poppy and Olipop, for example, contain added sugars in organic maple syrup, organic agave syrup, or similar sweeteners. At least they aren’t traditional sugars like sucrose or high fructose corn syrup, right? (NOT!) While these sweeteners seem like a sweeter and healthier deal, added sugar from maple syrup or honey or from high fructose corn syrup is still sugar. Sorry to break the bad news to you all.

For reference, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that men consume no more than nine teaspoons (36 grams or 150 calories) of added sugars per day and women consume no more than six teaspoons (25 grams or 100 calories). Be sure to track added sugars in all processed foods.

What about probiotics and breast milk?

Think about nursing and how taking probiotics can alter breast milk's composition. This brings to light how our eating impacts our health and sometimes the health of our babies. Although the extent and specific effects can vary and are not really known, probiotics consumed by the mother can potentially transfer to breast milk.

This transfer may introduce beneficial bacteria (probiotics) into the infant’s gut through breastfeeding, but it may potentially influence the infant’s gut microbiota composition and development. This may have implications for the infant's immune function, digestion, and overall health. Is this good or bad? Research is still evolving.

Natural sources vs. supplements.

We should think twice about introducing microbes in such high quantities into our diet, especially when breastfeeding. As an alternative, eat foods that are higher in microorganisms, such as fresh fruits and vegetables.

Other ways to naturally get microbes into your system are by

Eating fermented foods like kimchi and yogurt

Eating prebiotic foods that are high in fibers, like asparagus, bananas, and whole grains (bacteria love them)

Gardening and spending time getting your hands dirty in the soil. Soil has a diverse range of microbes and this, in turn, diversifies your microbiome!

Eating a diverse diet (variety is important), and

Owning pets. Yup - our furry friends share their little microbes with us 👀

Conclusion

My take is that sometimes ingesting a bolus of microorganisms is fine, especially when your gut has been depleted of microorganisms from serious bouts of flu or antibiotics.

But in general, if the microbiome ain’t broke, what’s there to fix?

If you’re serious about your gut health — get your poop checked for microorganisms before introducing new ones. 💩

Fecal analysis provides insights into the diversity and abundance of microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc.) in the gastrointestinal tract. This helps you understand the balance between beneficial and potentially harmful microbes. Then, we can think about what foods might help fill the gap.

Although the research is still unclear, ingesting a large number of microorganisms into our system now and then seems relatively safe. But doing it for the long term seems riskier because no one knows what this will do to us — could it alter us forever? Yikes, that’s a thought!

Suppose you decide probiotics are right for you.

It’s important for consumers to choose probiotics based on reputable brands that are inspected or undergo rigorous testing with transparent labeling that clearly identifies the strains and their potential benefits.

Are microbe-enhanced drink manufacturers trustworthy when they don’t have such rigorous testing? Let’s hope so.

It would be wise to find and consider consulting with healthcare professionals for personalized recommendations. But who is this? I have a hard time believing my conventional medicine providers would know much more than “they’re good for you” and give you general recommendations. Microbe types and interactions are beyond their expertise.

So, I would recommend asking pharmacists, dietitians, and herbalists who understand microbes directly, asking them, “How much do you know about microbes and probiotics?”

Tinkering with the microbes that our ancestors gave us on a large scale intuitively seems like a bad idea. But we simply don’t know what we don’t know.

Let’s consider this: Is ingesting and introducing billions of select microbes into our gut a good idea when we’re already healthy? How about when we’re not?

You’re in charge of your own health — keep yourself informed. Health heroes question everything, and go in with eyes wide open before making decisions.

Want to take a deeper dive into the topic? Here are a few links for recommended reading.

🐛 Can Probiotics Prevent Osteoporosis?

🧫 The Role of Probiotics in Human Health

What about you? Do you currently take supplements, drink kombucha, or eat a lot of kimchi? Leave a comment so I can hear from you — I’m always around in the comments section or DM’s if you have any questions or comments to share.

See you next week!

In good health,

Dr. Alice

A little more about Dr. Alice Burron and The Health Navigator Group:

You can find more about The Health Navigator Group at our website: www.thehealthnavigator.org

On Instagram: @the.health.navigator

And learn more about Dr. Alice Burron at her website: draliceburron.com

Or via her personal Instagram: @dr_burron

You can even connect with her on LinkedIn, if you want to be professional about it. 👓

And if you’re not subscribed to our Substack, what are ya doing? It’s free, and packed full of useful tools to help you on your journey to better, faster healing.